We are fast approaching that time in most students' lives: high school graduation. That time when 5 to 10 years of learning an instrument gets shoved under the bed with old Chemistry homework to gather dust.

No, no, no!!

There is musical life after high school!

Music is not just another subject to most students. There is a fair degree of self-motivation, external time committing, soul-baring and blood/sweat/tears that goes into learning an instrument. It is a shame to let that experience go to waste when there are places to go that are crying out for new musicians.

Along with all of the associated educational benefits of music, it is also a social endeavour. It crosses cultural and age barriers. It is a great source of stress-relief and a healthy hobby. After all, playing a musical instrument is on the list of activities that are known to contribute to the prevention or delay of dementia.

There are different levels of engagement in music once students finish high school. The first one is the one most people think of when they consider music past school: tertiary education.

Continuing to play your instrument at tertiary level is becoming much more commonplace with universities beginning to allow non-majors to participate in music courses and ensembles. If you are studying a content-heavy course and wish to earn credit in another area, check with your institution to see if they offer non-major involvement in the music program.

Outside of the education system, there are many community opportunities to stay involved in music. There are quite a few community bands and orchestras in most areas. Here are a few you might be interested in if you are in Perth:

Concert Bands (several of these have an auxiliary swing band):

Leeming Area Community Bands

Armadale City Concert Band

Mandurah Concert Band

Combined Districts Concert Band

West Australian Symphonic Wind Ensemble

City of Perth Bands

Perth Concert Band

Claremont Concert Band

Brass Bands:

Royal Agricultural Society of WA Brass Band (formerly Midland Brick)

Town of Victoria Park Brass Band

City of Perth Bands

Challenge Brass

Canning City Brass

Orchestras:

Fremantle Symphony Orchestra

Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra

Hills Symphony Orchestra

South Side Symphony Orchestra

I have played in a number of the bands and orchestras in Perth, and each one has a slightly different feel about it. Most bands are crying out for more players (especially clarinets, double reeds, low brass and percussion) and are happy to have you come along and try it out. Orchestras are always in need of string players and 'hard-to-staff' instruments such as double reeds, brass and percussion.

(If I forgot any, or you are involved in a community band/orchestra you would like included in this group, please email me and I will add it in.)

There are a number of community choirs popping up over Perth as well. Many now have Facebook pages or websites and it is worth Googling if you are interested in keeping the music alive.

If keeping to yourself is more your thing, or you are interested in a path of continued improvement, private lessons might be just the ticket. Some teachers work better with younger students, but others know how to work with adults - it is quite different. A good adult teacher understands how to work in with a busy working/studying life, and their expectations of you should not be vastly different to your own. They should listen to your areas of interest - this is less about the pure education of music and more about continuing the enjoyment of music. By the same token, you as a student should also realise that there are some things that teachers know are going to help you reach your goals, and some of them might not be as fun! Adults can also continue to take exams to give them a specific goal to reach - exams are not age-based. Perhaps this is a good time to start learning a second instrument, especially if you play an instrument that seems to be well-catered for in community ensembles already. This time around, you have the benefit of learning at your own pace without the pressure of exams, assessments and curriculum (also, the second instrument is MUCH easier than the first).

For the more-casual among us, there is the opportunity to organise regular 'rehearsals' of an ensemble of your choosing for the pleasure of playing through music (and occasionally wine may be involved). I have friends who have begun to play the recorder since their children have become involved in music, and have regular 'lunch and recorder ensemble' sessions with some like-minded friends. Get yourself a book of flexible ensemble rep and gather some friends together - sometimes music making without particular goals or expectations is the best kind.

Music - Play For Life!

Monday, December 30, 2013

Instrumental life after high school

Labels:

adults,

band,

community,

high school,

instruments,

orchestra

Monday, September 23, 2013

Step away from the tuner and no-one gets hurt!

Tuners are great little devices. And now, you can even have one in your pocket at all times with tuner apps available for your mobile device of choice. They are responsible for helping provide a consistent, stable pitch for ensembles to tune to via the oboe/tuba/pitch reference instrument in your ensemble. And they are the key to making sure you play in tune all the time - just stick one of these handy little suckers on your stand and try to avoid the red lights. Right?

Err, no.

I have seen doctoral students with them on their stand in rehearsals, annoying everyone around with the constant Christmas-tree-like flashing. I have seen entire bands performing on stage with their tuners clipped to their bells. And every time, I feel like music education has seriously let these people down.

There are both scientific reasons and educational reasons why this is a bad idea. The scientific reasons are all to do with a guy called Pythagoras. (Yes, the guy responsible for the theory behind calculating the length of the hypotenuse in a right-angled triangle. I told you there was maths in music.) It is widely believed that Pythagoras was largely responsible for discovering the natural division of the musical scale into 12 notes. He calculated the scale by using a string of a set length, and changing the length based on a ratio of 3:2. After repeating this process 11 times, he wound up back at the note he began at, albeit in a different octave. Except he didn't quite make it. The natural division of the scale, according to the ear and the maths, overshoots the octave slightly, meaning not all 12 notes fit neatly into the octave. The fifths, known as pure fifths, are pleasing to the ear, but the thirds sound rather interesting according to modern ears.

This didn't become an issue until about the 16th century, when the third came into prominence as the dominant interval, keyboards were being used and composers wanted to have the flexibility to write in all available keys. Several tuning systems were used around this time, including just intonation and well-temperament (J.S. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier was his way of introducing the tuning system as a way of writing in all 12 keys). Equal temperament was proposed in the late 16th century. It involved the division of the octave into 12 equal intervals. Equal temperament was easy for keyboard instruments, but it didn't allow for the natural 'settling' of certain intervals and the resonance that 'pure' intervals provide.

Tuners typically use equal temperament. If you are playing with piano, then this is not such a bad thing. If you are playing in an ensemble that relies on the natural harmonics of certain intervals, then by being 'correct' with the tuner, you are actually 'out of tune'. Fifths will sound squashed and major thirds will sound too open. Leading tones need to be raised slightly in order to create a sense of their true function.

There are tuners which claim to use just and mean temperament, but given that natural tendencies will always depend on the current harmony being sounded, how can any device possibly predict what the exact pitch of the note is that needs to be slotted in, given it does not know what pitches have already been given?

Pedagogically speaking, relying on tuners means students are training the eyes and not the ears. They know what to LOOK for but often have no idea what SOUNDS in tune. This coupled with the fact that the tuner is not, essentially, in tune with most ensembles, and it is no wonder these students have a confused ear.

Students should learn to identify sharp and flat against a unison pitch as a first step, and work at matching this as quickly as possible. Tuning fifths should follow soon after. Students should listen to eliminate beats, accentuate resonance and discover how to affect pitch on their instrument WITHOUT changing the pitch of their entire instrument by moving tuning slides and pegs for single notes. (Don't laugh. I have seen it more times than I can count.) Air speed, embouchure and finger adjustments/venting are the main players here.

So, the tuner is a handy little tool, but it is not a crutch. Overused, it will do more damage than good. Trust yourself to rely on your ears, and you will be surprised how much you are innately aware of.

|

| No, you are probably not. |

I have seen doctoral students with them on their stand in rehearsals, annoying everyone around with the constant Christmas-tree-like flashing. I have seen entire bands performing on stage with their tuners clipped to their bells. And every time, I feel like music education has seriously let these people down.

There are both scientific reasons and educational reasons why this is a bad idea. The scientific reasons are all to do with a guy called Pythagoras. (Yes, the guy responsible for the theory behind calculating the length of the hypotenuse in a right-angled triangle. I told you there was maths in music.) It is widely believed that Pythagoras was largely responsible for discovering the natural division of the musical scale into 12 notes. He calculated the scale by using a string of a set length, and changing the length based on a ratio of 3:2. After repeating this process 11 times, he wound up back at the note he began at, albeit in a different octave. Except he didn't quite make it. The natural division of the scale, according to the ear and the maths, overshoots the octave slightly, meaning not all 12 notes fit neatly into the octave. The fifths, known as pure fifths, are pleasing to the ear, but the thirds sound rather interesting according to modern ears.

This didn't become an issue until about the 16th century, when the third came into prominence as the dominant interval, keyboards were being used and composers wanted to have the flexibility to write in all available keys. Several tuning systems were used around this time, including just intonation and well-temperament (J.S. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier was his way of introducing the tuning system as a way of writing in all 12 keys). Equal temperament was proposed in the late 16th century. It involved the division of the octave into 12 equal intervals. Equal temperament was easy for keyboard instruments, but it didn't allow for the natural 'settling' of certain intervals and the resonance that 'pure' intervals provide.

Tuners typically use equal temperament. If you are playing with piano, then this is not such a bad thing. If you are playing in an ensemble that relies on the natural harmonics of certain intervals, then by being 'correct' with the tuner, you are actually 'out of tune'. Fifths will sound squashed and major thirds will sound too open. Leading tones need to be raised slightly in order to create a sense of their true function.

There are tuners which claim to use just and mean temperament, but given that natural tendencies will always depend on the current harmony being sounded, how can any device possibly predict what the exact pitch of the note is that needs to be slotted in, given it does not know what pitches have already been given?

Pedagogically speaking, relying on tuners means students are training the eyes and not the ears. They know what to LOOK for but often have no idea what SOUNDS in tune. This coupled with the fact that the tuner is not, essentially, in tune with most ensembles, and it is no wonder these students have a confused ear.

Students should learn to identify sharp and flat against a unison pitch as a first step, and work at matching this as quickly as possible. Tuning fifths should follow soon after. Students should listen to eliminate beats, accentuate resonance and discover how to affect pitch on their instrument WITHOUT changing the pitch of their entire instrument by moving tuning slides and pegs for single notes. (Don't laugh. I have seen it more times than I can count.) Air speed, embouchure and finger adjustments/venting are the main players here.

So, the tuner is a handy little tool, but it is not a crutch. Overused, it will do more damage than good. Trust yourself to rely on your ears, and you will be surprised how much you are innately aware of.

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

The musical diet - ensemble edition

If you take an ensemble, you need to be able to answer these questions with an even stronger 'yes'. Ensemble repertoire is big business. Composers are now employed by publishing companies and must meet targets, regardless of whether the piece is inspired or required.

In the case of recent band music, it is often described as being 'assembly-line'. A lot of these works follow the same formula. Fast, rhythmically driving A section. Slow, lyrical B section, often in a related key, a change in time signature (often to 3/4) with perhaps the melody stated initially by a flute or oboe solo. The fast A section returns, usually slightly abridged to finish with a dramatic all-timpani-blazing coda.

I see you nodding.

We need to give our kids a good diet to ensure they turn out as well-rounded musicians. The above mentioned pieces are fine - if you mix them up with other stuff. There is still educational benefit to be had if you know how to work the concepts.

The kinds of repertoire that our ensemble students should be exposed to include:

In the case of recent band music, it is often described as being 'assembly-line'. A lot of these works follow the same formula. Fast, rhythmically driving A section. Slow, lyrical B section, often in a related key, a change in time signature (often to 3/4) with perhaps the melody stated initially by a flute or oboe solo. The fast A section returns, usually slightly abridged to finish with a dramatic all-timpani-blazing coda.

I see you nodding.

We need to give our kids a good diet to ensure they turn out as well-rounded musicians. The above mentioned pieces are fine - if you mix them up with other stuff. There is still educational benefit to be had if you know how to work the concepts.

The kinds of repertoire that our ensemble students should be exposed to include:

- Works by a variety of composers of different nationalities

While there is not much educational about playing entirely 'typical' mass produced band pieces as described above, there is also not much in a season of only Mozart. Variety is the key. On a side note, if you have students who happen not to like Mozart, you are turning them off orchestra all together. At least give them a variety that means they will have a chance at liking something else!

- Works in a variety of forms.

Lots of students will graduate high school having never played a multi-movement ensemble piece. Or a piece in sonata form. Or a fanfare. Get out of the ABA fast-slow-fast comfort zone and present something with new structural concepts. I taught two Year 10 students the other day, and as we were working through Mozart's Turkish Rondo, I had to explain rondo form, as they had never heard of it before. Year 10! 5 years of learning instrumental music!

- Works in something other than major keys.

There is a lot of modern band music that is not in major keys - and it is in the natural minor (which is a cop out, because the natural minor is just a major scale starting two notes lower). The reason for this is due to the system of learning in the US, which involves starting all together in band, with flat keys being the dominant theme. You can't even play in F minor as they don't learn concert E natural for at least the first year (and then composers avoid it because the kids aren't used to playing E naturals and they don't want their piece to be played badly).

Find music in modes. Music in true melodic and harmonic minors. Music that is chromatic and music that constantly changes its tonal centre.

- Which also applies to time signatures.

4/4 is a boring but necessary evil. Overdone, it allows kids to fall into a comfort zone and approximate the music instead of concentrating on the exactness of rhythm. 6/8 is a must, as is 3/4. Students shouldn't leave high school without having played in 5/4 or 7/8. Teach students about subdividing uneven bars - best they do it while they are young and learn to feel it. Choose at least one piece that changes time signature.

- Works with an historical context.

This is much easier in some areas than others, but it is still not uncommon to find choirs singing pop medleys and little else, or string orchestras playing nothing but the latest "insert publisher here" catalogue. Find out what the masterworks are for your ensemble. Are there easier arrangements for young bands? Are there other pieces by those composers that you could expose your students to?

Too many band students are graduating high school without even knowing that Holst wrote the first* band piece, and that it's actually really cool. How about all of those guys from the 1950s? Until I went to the US, I knew nothing about Vincent Persichetti and Morton Gould, and I had played in bands for nearly 20 years!

So...where do I find all this music?

Publishers tend to advertise and sell the latest unless you know what you are looking for. Here is a list of places to check out repertoire of note:

- Festival lists - make sure these come from a variety of places around the world! Many are now available online.

- Annotated guides and repertoire books - choose those written by respected educators and conductors. For orchestra and band, check out the GIA series "Teaching Music Through Performance in...", which comes with CDs as well.

- Specific forums and websites

- Advice from fellow conductors and organisations (ABODA, ASTA, etc)

It is our responsibility as educators to provide our students with a balanced diet. They only know what we open them up to, so make it worthwhile!

*I know there are other 'band' works before 1909, but Holst's instrumentation was the closest thing to our modern day band at that point in time, features idiomatic wind writing and was written specifically for 'military band', and is therefore considered the first true wind band work.

Labels:

appropriate,

band,

choir,

educational,

orchestra,

repertoire

Friday, September 6, 2013

Fix my oboe reed (aka: 'why does no one want to sit next to me in band?')

I love oboe. It gets the best solos, it gets to tune the entire orchestra and not that many people play it, so there are lots of opportunities to play.

BUT...

Those darn reeds! They will make or break a player - often in the same rehearsal.

How can you help yourself out here? Unlike clarinet and saxophone (and there are single-reed pros out there who will also insist that this isn't the case), machine made reeds just don't cut it, and you can't select from a box of 10. The ideal situation is to learn how to make them yourself. Initial costs can be expensive, but once you are set up, the cost per reed is much cheaper than buying them. Making reeds is not 'hard', but it does require attention to detail, trial and error and you will need to learn that you will make some horrendous sounding 'reeds' before you can start making useable ones. Like learning the instrument itself, it is a process. (If you think you are at this point, I offer reed making lessons).

If making reeds isn't yet on your to do list, you still need to learn how to adjust them and look after them. There are a few guidelines to get started on this journey.

1. Make sure you always have multiple WORKING reeds. Three is a minimum. Rotate them each time you play, and try to have reeds in your case that are of various ages, so they don't all die at once. Which leads me to...

2. Keep them in a case. A good case. Cases can be expensive, but so are reeds - look after them! Cases with ribbon holders (reeds fit into a slot), as opposed to mandrel holders (reeds slide onto a stem), are best, as reeds that do not fit the mandrels correctly can slide off and damage their tips on the inside of the case (learnt from experience). Your reed case should have a place for at least 6 reeds, or 20 if you make your own reeds. Make sure your reed case has ventilation, and regularly keep the lid open if you have been playing a lot in order to allow the reeds to dry properly. Constantly wet reeds can attract mould and will die faster.

3. Learn how to adjust your reeds and get the tools needed for the job.

Adjusting reeds

The minimum tools you will need for this job are:

BUT...

Those darn reeds! They will make or break a player - often in the same rehearsal.

How can you help yourself out here? Unlike clarinet and saxophone (and there are single-reed pros out there who will also insist that this isn't the case), machine made reeds just don't cut it, and you can't select from a box of 10. The ideal situation is to learn how to make them yourself. Initial costs can be expensive, but once you are set up, the cost per reed is much cheaper than buying them. Making reeds is not 'hard', but it does require attention to detail, trial and error and you will need to learn that you will make some horrendous sounding 'reeds' before you can start making useable ones. Like learning the instrument itself, it is a process. (If you think you are at this point, I offer reed making lessons).

If making reeds isn't yet on your to do list, you still need to learn how to adjust them and look after them. There are a few guidelines to get started on this journey.

1. Make sure you always have multiple WORKING reeds. Three is a minimum. Rotate them each time you play, and try to have reeds in your case that are of various ages, so they don't all die at once. Which leads me to...

2. Keep them in a case. A good case. Cases can be expensive, but so are reeds - look after them! Cases with ribbon holders (reeds fit into a slot), as opposed to mandrel holders (reeds slide onto a stem), are best, as reeds that do not fit the mandrels correctly can slide off and damage their tips on the inside of the case (learnt from experience). Your reed case should have a place for at least 6 reeds, or 20 if you make your own reeds. Make sure your reed case has ventilation, and regularly keep the lid open if you have been playing a lot in order to allow the reeds to dry properly. Constantly wet reeds can attract mould and will die faster.

3. Learn how to adjust your reeds and get the tools needed for the job.

Adjusting reeds

The minimum tools you will need for this job are:

- A knife (bevelled knives are easiest for students to sharpen - cheaper knives are available from Rigotti, and as you progress, you can get a better quality knife, such as a Landwell, my knife of choice). Make sure that if you get a bevelled knife that you get the correct hand - they are specific to left and right hand use. Other kinds of knives include hollow ground, double hollow ground and razor.

- A plaque - this is a small piece of plastic/metal/wood that sits between the blades of the reed so that it doesn't collapse and crack under the pressure of scraping. You should have a flat and a contoured plaque (I keep several of each as they are small and easy to lose)

- A pair of flat-nosed craft pliers (if your reeds come with wire on them)

- Razor blades

- A cutting block - choose one which is not too small and has a gentle curvature on top

- Plumbers' tape

You will notice that some of these items you will find in non-music stores. The double reed specific items can sometimes be found in your local music store, but you will have more choice in brands, styles and prices if you shop around online.

So I have the tools...what do I do with them?

The best way to learn how to adjust reeds is to practice your techniques on old dead (or almost dead) reeds. You don't want to go messing up your working ones if you aren't sure what you are doing!

The first thing you need to do is learn how to scrape. Put a plaque in between the blades of your reed (don't push it in too far or you may wind up making the reed leak). Hold the reed in your left hand (reverse all instructions if you are left handed). Support the blades from underneath with your left index finger and stabilise the reed on top using the joint of your left thumb. Place the knife perpendicular to the reed, support the top of the knife blade with the tip of your left thumb, and use a forward-moving swinging motion to gently scrape cane towards the tip. Do this a few times on a dead reed to get used to the feeling of just scraping. Try scraping at different angles - straight down the centre of the reed to the tip, along the rails (the sides) to the tip, and on a diagonal towards the corners of the tip. You will soon learn how hard you can push before you either crack the reed or leave gouges in the cane. Always work in good light (LED or fluorescent light tends to show up the imperfections the best).

Here are some basic adjustments to try. Note that these adjustments apply to European (short) scrape reeds only, which is the most common type of oboe reed used in Australia.

Reed too soft: Firstly, start by using your pliers to gently squeeze the sides of the wire, opening up the tip. If this doesn't help, or makes the reed too fuzzy, return the wire to the opening it originally had. Try scraping the rails (sides) a bit thinner - this tricks the reed into thinking it has more 'meat' in the middle than it does. If it still needs more and the sides are looking a bit thin, the last resort is to clip the tip using a razor blade and cutting block. Make sure you soak the reed for several minutes before doing this otherwise it will crack. Take as small a slice straight across the tip as you possibly can (like a hair width), trying the reed between each clip. You will be amazed at how much of a difference such a small amount can make!

Reed too hard: Start with your pliers and gently squeeze the wire a little more closed. If this doesn't work, return the wire to the original opening and try doing a gentle 'all over' scrape. Be wary of taking too much from the heart, which is the area in the centre of the reed below the tip. I like to scrape from the bottom left corner of the U all the way to the right corner of the tip, and repeat from right to left. This prevents all the scrape coming out of the heart.

Can't play low notes: Low notes are almost entirely to do with the base of the scrape, the U. Scrape a little deeper at the absolute base and taper the scrape as you go higher, focusing mostly on the sides of the U. This technique will also lower the pitch of a sharp reed. Be careful to test as you go, because if you take out too much, you will affect the high notes. If you are still not able to play low notes, the reed may be just a little hard in general.

Reed is flat: Clip the tip of the reed and make the tip a little thinner/longer if it needs it (i.e. if it wasn't too soft to start with).

Reed sounds like a duck/has a shrill sound: Scrape only the corners of the tip (preferably on a diagonal) very gently. Make sure the scrape follows through past the tip - you do not want a ridge left behind. Do not take any cane out of the heart or the middle of the tip as you will only make the problem worse!

Reed is resistant even though it seems soft enough/the cane seems thin enough: This usually means there is a leak between the two blades, which you can sometimes see in good light. If your reeds are wired, this is less common, but it can still happen. Use a very small amount of plumbers tape (about 2cm) and wrap around the reed, using half the thickness to cover the thread and the other half to cover the base of the reed. If this still doesn't fix the problem, try scraping the extreme tip (i.e. the last 0.1mm) a little thinner. Resistance can sometimes mean a reed is dead. Leaks can also occasionally 'repair' themselves with changes in weather - if none of the above fixes the issue, put the reed away and try again next season.

* * *

With practice, you will get better at identifying the problem and being able to match the correct fix to it. Don't put up with (or throw out) half-working reeds, adjusting them is a much better solution!

Labels:

adjusting,

band,

maintaining,

oboe reeds,

students,

tools

Friday, August 30, 2013

The musical diet - solo instrumental edition

Repertoire can become a contentious issue among teachers. There are so many things to consider in order to provide appropriate repertoire. If you can hold up repertoire and answer yes to these questions, then your repertoire stands up to the test.

This becomes awkward for those of us who teach in small groups. The ideal situation is that those groups be as close in level as possible. If this is not the case, here are some strategies for dealing with repertoire:

Add challenges to the existing repertoire. Some students are struggling, but others are sailing through, so add in a new teaching point (perhaps some trills or other ornamentation at cadence points, create more complicated rhythms) or use those composition and harmony skills to create a counterpoint/duet part or an introduction.

Provide a 'challenge for the week'. This is more applicable to younger students who are working from method or repertoire books. If most students are just coping with the assigned work, give out a 'challenge piece', a non-compulsory section of the practice for the week which is pitched well above the current work. (I often don't even give this to the student in question, but the group in general. The students know who the strong one is and do not need it spelled out to them every week.) In this case, depending on the student, it is often okay to provide something pitched much higher than the current work and with concepts they may need to research themselves (a new note, etc).

Provide extra material for the student on a long term basis. This might be a separate piece, it might be a different book entirely. You may choose to hear the student play through it every few weeks (perhaps even during pack up time or before lessons start). It is good to have a knowledge of what is available outside the standard repertoire and books you use just for this purpose.

There is nothing wrong with Disney playalongs at all (I find them quite educational in that the students are excited to play them, and therefore practice them, and they often use techniques that students may otherwise have shied away from). But they need to be presented alongside scales, technique building and repertoire that has artistic merit.

The best teachers can pull concepts from almost any repertoire. In reality, we should be using repertoire which already has these concepts built in. This particularly applies to students still in the early developmental phase of learning their instrument.

Students need relevancy. If you are going to teach them about semiquavers, back it up with repertoire that includes semiquavers. I often find myself bouncing around a book rather than just blindly following it in order as I like to ensure I am following a path of consistent progression and I like to keep all the 'relevant' repertoire together.

Try to extract extra educational points from the repertoire. Give students the task to find out 5 facts about Mozart during the week you are doing Symphony no. 40. Explain why so many pieces are called 'Minuet'. Demonstrate how a sequence works when it appears and why it is helpful to recognise patterns like that.

There are teachers who insist on sticking to their guns and teaching every student as though they are only ever going to play in lessons. In reality, those students become disadvantaged and frustrated when they can't understand why the band director is picking on them for not knowing the notes. As educators on those instruments, it is important we set the students up for success in whatever environment they find themselves in. If this means creating worksheets and exercises to fill in the gaps that your chosen tutor book doesn't cover, then go for it!

This definitely applies to areas other than band. Your student has been asked to play at their church - do you help them with the music and perhaps give them extra materials to help with any difficult concepts, or do you tell them it's not part of the plan? Some students will always be attracted to performing publicly - make sure they have touched on repertoire that can be used for this purpose. School wants an assembly item? Head off any disasters by making sure students have had a chance to play ensemble music in lessons before you present them with the duet they are going to play in front of the school. Students' instrumental learning needs to be transferrable or it loses relevancy and meaning.

Does your repertoire stand up to the test? Good repertoire is equally as important as good teaching - get the best tools for the job!

- Is it at an appropriate level?

This becomes awkward for those of us who teach in small groups. The ideal situation is that those groups be as close in level as possible. If this is not the case, here are some strategies for dealing with repertoire:

Add challenges to the existing repertoire. Some students are struggling, but others are sailing through, so add in a new teaching point (perhaps some trills or other ornamentation at cadence points, create more complicated rhythms) or use those composition and harmony skills to create a counterpoint/duet part or an introduction.

Provide a 'challenge for the week'. This is more applicable to younger students who are working from method or repertoire books. If most students are just coping with the assigned work, give out a 'challenge piece', a non-compulsory section of the practice for the week which is pitched well above the current work. (I often don't even give this to the student in question, but the group in general. The students know who the strong one is and do not need it spelled out to them every week.) In this case, depending on the student, it is often okay to provide something pitched much higher than the current work and with concepts they may need to research themselves (a new note, etc).

Provide extra material for the student on a long term basis. This might be a separate piece, it might be a different book entirely. You may choose to hear the student play through it every few weeks (perhaps even during pack up time or before lessons start). It is good to have a knowledge of what is available outside the standard repertoire and books you use just for this purpose.

- Is is balanced?

There is nothing wrong with Disney playalongs at all (I find them quite educational in that the students are excited to play them, and therefore practice them, and they often use techniques that students may otherwise have shied away from). But they need to be presented alongside scales, technique building and repertoire that has artistic merit.

- Is it educational?

The best teachers can pull concepts from almost any repertoire. In reality, we should be using repertoire which already has these concepts built in. This particularly applies to students still in the early developmental phase of learning their instrument.

Students need relevancy. If you are going to teach them about semiquavers, back it up with repertoire that includes semiquavers. I often find myself bouncing around a book rather than just blindly following it in order as I like to ensure I am following a path of consistent progression and I like to keep all the 'relevant' repertoire together.

Try to extract extra educational points from the repertoire. Give students the task to find out 5 facts about Mozart during the week you are doing Symphony no. 40. Explain why so many pieces are called 'Minuet'. Demonstrate how a sequence works when it appears and why it is helpful to recognise patterns like that.

- Is it preparing the students for others areas of their musical education?

There are teachers who insist on sticking to their guns and teaching every student as though they are only ever going to play in lessons. In reality, those students become disadvantaged and frustrated when they can't understand why the band director is picking on them for not knowing the notes. As educators on those instruments, it is important we set the students up for success in whatever environment they find themselves in. If this means creating worksheets and exercises to fill in the gaps that your chosen tutor book doesn't cover, then go for it!

This definitely applies to areas other than band. Your student has been asked to play at their church - do you help them with the music and perhaps give them extra materials to help with any difficult concepts, or do you tell them it's not part of the plan? Some students will always be attracted to performing publicly - make sure they have touched on repertoire that can be used for this purpose. School wants an assembly item? Head off any disasters by making sure students have had a chance to play ensemble music in lessons before you present them with the duet they are going to play in front of the school. Students' instrumental learning needs to be transferrable or it loses relevancy and meaning.

Does your repertoire stand up to the test? Good repertoire is equally as important as good teaching - get the best tools for the job!

Labels:

appropriate,

educational,

instrumental,

learning,

repertoire

Thursday, August 15, 2013

Music in education...why?

On Monday, Australian conductor and music education advocate Richard Gill published this article.

In this current world of standardised tests and, interestingly, what seems like an ever-decreasing amount of desk time for students as the curriculum becomes loaded with 'school responsibilities', why are people such as Richard Gill advocating for mandatory inclusion of music in the school curriculum? There are plenty of reasons (often given by administrators) as to why we shouldn't have music - time, space, funding and specialist teachers are the ones heard most often by those of us in this business.

Music is one of the few subjects which crosses into every learning area.

Music is an art.

This one is a given. It is creative. It demands artistry. It requires a mix of technique and emotion.

Music is a science.

How is sound produced by simply running a bow across a string? What is pitch, and how does a student identify or define it? Without science, and the integration of scientific concepts into the learning of an instrument, there is no music.

Music is a language.

Many musical terms are in Italian. Some are in French or German. The reading of music itself is another language that students must learn in order to engage in music. Whether it is traditional written music, or Kodaly method sol-fa, there is language to learn and apply. Students who don't even speak the same language can communicate through music.

Music is maths.

Music consists of pulse. In pulse, there are divisions. There is also measurement. The rhythm of western music relies on the division and multiplication of basic pulse by two (basic symbols exist for notes with beat lengths of 8, 4, 2, 1, 1/2, 1/4, etc). Students must apply fractions and ratios. Students must understand how tempo relates back to real time.

Music is a social science.

Music is present in every culture. And culture is present in music. Students studying music history will learn about some of the great composers and works that were linked with major world events. Cultures have distinctive musical styles which students learn to associate. Ethnomusicology is becoming a large branch of Western musical understanding, and is finding its way into classrooms.

Music is technology.

If there was ever an area of study that was evolving as fast as technology could keep up with it, music would be it. Music students are using smartphone apps in their practice and lessons (tuners and metronomes) and software in their classes (notation, sequencing, editing). They are downloading, recording, streaming and creating music. Music and technology are like peas in a pod, and the two help students link what they consider 'relevant' to their studies. It enables them to stay engaged as it builds on what they know and understand.

Music is a sport.

There is a physical-ness to making music. Singing and playing wind instruments requires good breath control and capacity. Some instruments are kinetically demanding, such as bowed strings and percussion. There is motion in all of music. Playing an instrument requires high degrees of coordination and fine-motor skills.

A subject that crosses this many learning areas must surely make for a balanced curriculum. It is a way of validating those learning areas which are often kept so cleanly in their pigeon holes by showing students that they have real world applications.

Aside from providing a balance and spread to the curriculum, we must make mention of the other important life skills that music provides. It encourages teamwork. Students must work together to stay in tune and in time. There is often no 'leader' and no one person should 'stick out' all of the time. Students must be relied on to pull their weight and not let the team down. At the same time, there can be opportunities for leadership and mentorship. Music is one of the few areas in school where students from multiple year groups work together. Students learn to work with others older and younger than them, and adjust accordingly. Responsibility is another valuable skill - being responsible for your team, for your instrument and music, for your schedule and for your own learning.

Music not only provides a balance to the curriculum, it provides support. In this academic-focused era that we are in, should we not invest in something that has been proved many times to improve student learning and results? The so-called Mozart effect is real. In addition to the research, enough evidence lies with the musical prowess of the schools with renowned academic results. If you look at the schools with the highest-level ensembles in any school band, orchestra or choir festival, then compare it with a list of the top performing schools in leaving exams, there will be a correlation. While it might be thought of as a chicken-and-egg scenario, there is no denying that the link exists.

Consider the investment in your child's music education. If your school does not have a music program, ask why not. If your school does have a music program, encourage your child's participation and support wherever possible.

I will leave you with this little gem that has been floating around social media:

Labels:

advocacy,

curriculum,

learning areas,

music education,

Richard Gill

Friday, August 9, 2013

Scales are like vegetables...

...you might not like them, but they're good for you.

Anyone who has ever been a student of mine will have heard me utter this every time I sense a complaint about scales is about to occur. Younger students often don't understand why we do scales, but have often had the vegetable rule drilled into them from a young age!

Scales (and other technical work) are necessary for development and progression. Teachers don't just make students do them because they are mean and because they had to do them when they were that age. We do scales because:

Anyone who has ever been a student of mine will have heard me utter this every time I sense a complaint about scales is about to occur. Younger students often don't understand why we do scales, but have often had the vegetable rule drilled into them from a young age!

Scales (and other technical work) are necessary for development and progression. Teachers don't just make students do them because they are mean and because they had to do them when they were that age. We do scales because:

- Lots of music contains fragments of scales and other technical passages

- Scales help cement certain finger and/or embouchure changes (i.e. you don't have to wait until a hard fingering passage turns up in a piece of music and THEN have to worry about how to do it, because you've already worked it out!)

- Scales are good for warming up fingers, mouth, air and brain before we play music

- Scales are a good way of learning and using new notes as soon as we learn them

Most students will take this with a grain of salt. Even if the idea of scales 'makes sense', there is still the perception that 'scales are boring'.

If you have to eat vegetables, you want them to be in the tastiest form with the most variety possible, right?

If you are stuck in the 'scales are boring' mindset, try these tricks:

- Write all the scales you know (or need to know) on small pieces of paper. Do the same with the rhythms/speeds/articulations you are playing, but keep them separate. Draw one from each pile - this will match up a random scale with a random style and keep each scale fresh and interesting.

- Still on rhythm - find an interesting rhythm in one of your pieces (or invent one) and play all your scales in this rhythm. Not only does it become a new challenge all by itself, it is MUCH more exciting than straight quavers.

- If you ever have chance to warm up with others (in group lessons, mass warm-up sessions, etc), play scales in rounds. Leave a two-note gap between players. The harmonies it creates are glorious!

- Play all of your scales from the top downwards, then back up. This is surprisingly harder than it sounds, and is more often than not the cure for those who can play scales brilliantly on the way up but fumble on the way down (believe it or not, this is extremely common).

- Speed challenge - think of this like a scale version of the beep test. There are so many ways of doing this - you could focus on one scale in one session and use your metronome to see how fast you can get, or perhaps take a set of scales at a set speed and advance by 5bpm or so each day.

- Create melodic patterns with your scales. A common one, using C major as an example, is [C D E F, D E F G, E F G A, etc]. Another is [C D E C, D E F D, E F G E, etc]. Not only is this more interesting than simply running up and down aimlessly, but some of these patterns often turn up in pieces, particularly Baroque and Classical music. You can even use the order of the notes in the scale to create random patterns, trying to stay in order at all times.

- Learn a couple of 'cool' scales such as modes and blues scales to scatter amongst your 'everyday' scales (if these are not already your everyday scales).

We still need to know our scales in their original form for assessments, exams and general knowledge. But these techniques, interspersed with standard scales, not only relieve the boredom that scales can induce, but may also help in the long run.

Happy technique-building!

Labels:

fun,

scales,

teaching tips,

technical work

Saturday, May 25, 2013

Instrumental teachers and their students - a love story

As I prepare to leave the US in less than 5 days, I have had to say good bye to the students I have taught here. It has been much tougher on me than I somehow expected.

I have farewelled hundreds of students in my time, but it is different this time. My students in the past often still live in the area. They graduate or leave for high school, and I am just a part of their journey, a part that just moves through life along with everything else. I still see 'old' students at the shops, attending concerts of younger siblings, on Facebook (once they have graduated high school, of course) and in community ensembles (which is fantastic to see!)

I am leaving the US in this capacity. I don't doubt that I will be back, but it certainly won't be with the same intent. There is a good chance I will never see these students again. I was the one who started them on their musical journey, or was a helping hand when school band got too much, or provided support when they made the decision as an adult to once again learn the instrument they played in school. They aren't leaving or going anywhere, they haven't reached a transitional phase. It's me who is moving on from them, not the other way around, and I come to love my students so strongly that I feel as though I am abandoning them.

Instrumental music tuition is what I do and love, and it creates such a special bond with a student. I have taught in many different arenas and circumstances, and the bond you create with your instrumental teacher is not one you can replicate in any other area. It is not better or worse, it's just different.

I have taught classes of students - I have taught dance (both to dancers and beginner high school students), I have taught class music. I have even taught sport (if you know me, you will know that this is the most hilarious and ironic thing I could have taught. My high school Phys Ed teachers would die of laughter if they knew what my country posting consisted of). You can develop beautiful relationships in these classes - you can encourage teamwork, you observe progression, you watch friendships develop, you gain trust and respect.

What makes instrumental music instruction different?

I have farewelled hundreds of students in my time, but it is different this time. My students in the past often still live in the area. They graduate or leave for high school, and I am just a part of their journey, a part that just moves through life along with everything else. I still see 'old' students at the shops, attending concerts of younger siblings, on Facebook (once they have graduated high school, of course) and in community ensembles (which is fantastic to see!)

I am leaving the US in this capacity. I don't doubt that I will be back, but it certainly won't be with the same intent. There is a good chance I will never see these students again. I was the one who started them on their musical journey, or was a helping hand when school band got too much, or provided support when they made the decision as an adult to once again learn the instrument they played in school. They aren't leaving or going anywhere, they haven't reached a transitional phase. It's me who is moving on from them, not the other way around, and I come to love my students so strongly that I feel as though I am abandoning them.

Instrumental music tuition is what I do and love, and it creates such a special bond with a student. I have taught in many different arenas and circumstances, and the bond you create with your instrumental teacher is not one you can replicate in any other area. It is not better or worse, it's just different.

I have taught classes of students - I have taught dance (both to dancers and beginner high school students), I have taught class music. I have even taught sport (if you know me, you will know that this is the most hilarious and ironic thing I could have taught. My high school Phys Ed teachers would die of laughter if they knew what my country posting consisted of). You can develop beautiful relationships in these classes - you can encourage teamwork, you observe progression, you watch friendships develop, you gain trust and respect.

What makes instrumental music instruction different?

- We work one-on-one with a student (or sometimes in small groups). We learn all about that one student, and apply what we know to the context of a lesson. The lesson and the progress is tailored to the student. If the student is having an off day, we can change direction that day and come back the next week refreshed. If there is a concept that is proving more challenging than usual, we can spend more time with it, or come back to it later. Most importantly, when you work one-on-one with a student, you learn the whole student, not just what they are working on.

- We work in an area that is passionate, creative and cognitive. Music fits into every learning area - it is artistic, linguistic, cultural and scientific. We help students across so many areas, and it isn't uncommon to see changes in other areas of life when music becomes involved. Music is a way of baring the soul. You are learning a new skill that only you have control of, and we love the fact that students can be comfortable enough with us that this can happen.

- We are a constant in an ever-changing world. In private instruction, we continue to give lessons whether the student is moving from primary to high school, having relationship breakdowns, changing jobs, welcoming a new sibling or moving house. Being a point of stability inspires us to keep our teaching relevant and reliable. It is also wonderful being able to observe the growth of a student through life's challenges as an outsider - as a person and as a musician.

One of the most wonderful parts of the job, for me, is watching a student become as passionate as I am about music. This can take so many forms. One that always stands out is seeing students graduate high school (or start an instrument as an adult), and then play next to you in a community band. Music hasn't necessarily become a career, as it won't for many instrumentalists. But it is a passion that will continue to be explored. At this point, I realise that I have fulfilled my job as a teacher - I have instilled passion in my students.

Labels:

instrumental teaching,

leaving,

relationships,

students

Monday, May 20, 2013

Oboe reed cases

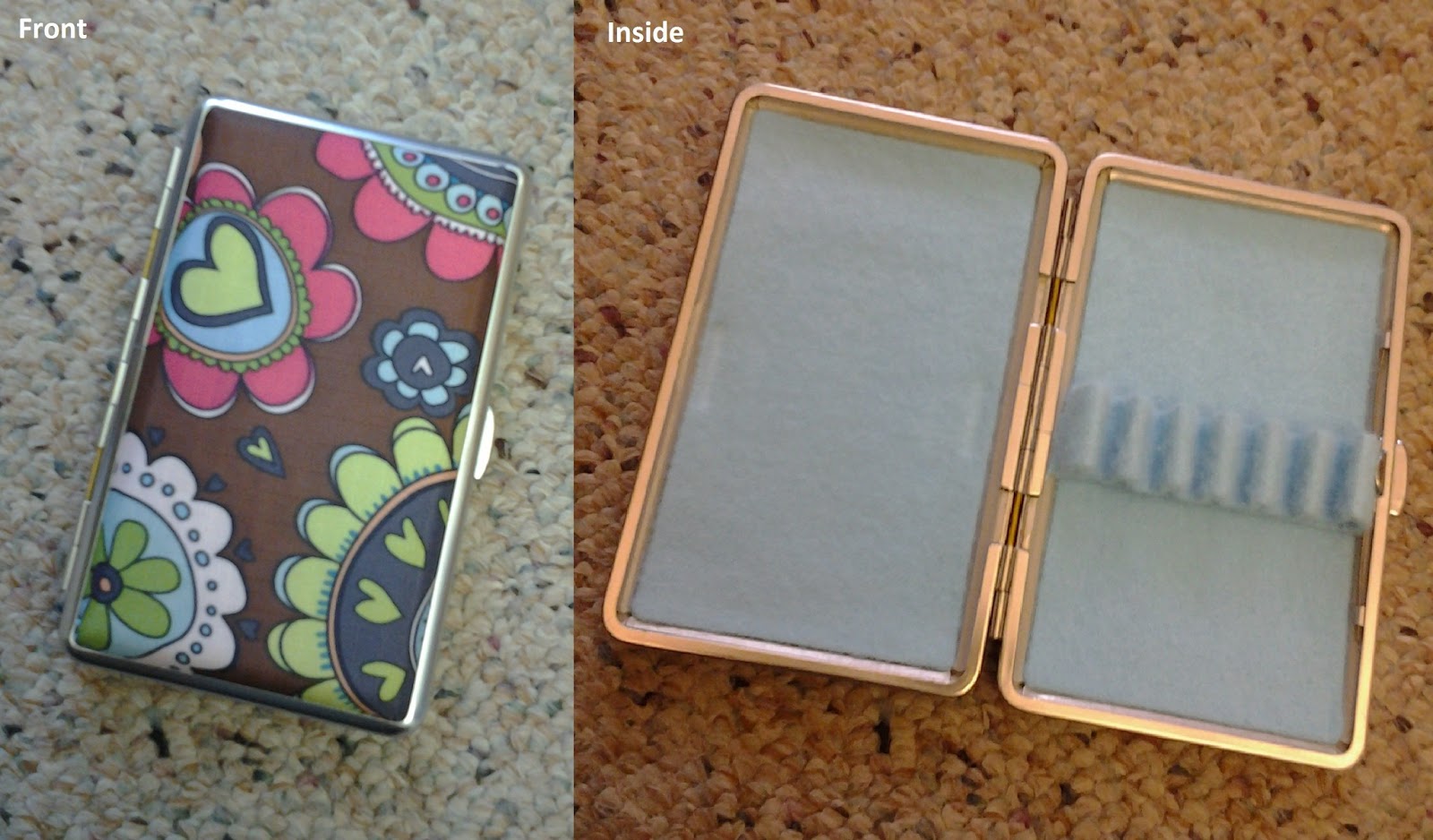

A shameless plug for my wares...

I leave the US in 10 days...and I'd love to sell my current inventory of oboe reed cases before I leave!

I have:

4 cases for 20 reeds $35

1 case for 14 reeds $30

1 case for 6 reeds $20

I can ship (standard shipping prices will apply) if needed. PayPal available!

If you are in Australia, I will have other designs available (and may have some of these left) after June, or I can hold one of these designs for you.

Contact me here at the blog, on the WindWorks Facebook page (link to the right of this post), or at rachel.found@gmail.com.

I leave the US in 10 days...and I'd love to sell my current inventory of oboe reed cases before I leave!

I have:

|

| Case for 6 reeds |

1 case for 14 reeds $30

1 case for 6 reeds $20

I can ship (standard shipping prices will apply) if needed. PayPal available!

|

| Cases for 20 reeds |

If you are in Australia, I will have other designs available (and may have some of these left) after June, or I can hold one of these designs for you.

|

| Case for 14 reeds |

Contact me here at the blog, on the WindWorks Facebook page (link to the right of this post), or at rachel.found@gmail.com.

Thursday, May 16, 2013

If the shoe fits...How to choose the right wind instrument

Perhaps your child has shown an interest in learning an instrument, or a teacher has identified musical promise. Maybe you want to start learning as an adult because you didn't get the chance as a youngster. Quite often, if you haven't had much exposure to music (and even if you have!), it is easy to be attracted to the look and sound of an instrument, but it may turn out that actually playing the instrument is not a good fit. Here's a quick guide to instruments, their use and their ups-and-downs to help you decide which way to go.

Caveat: It is possible for one's 'musical' personality to be vastly different to their 'person' personality. Someone who is passionate about an instrument that may not look to be a good fit on paper is still likely to do well with the correct training and attitude. But if you are undecided, these are merely some associations that can be made with each instrument.

Caveat: It is possible for one's 'musical' personality to be vastly different to their 'person' personality. Someone who is passionate about an instrument that may not look to be a good fit on paper is still likely to do well with the correct training and attitude. But if you are undecided, these are merely some associations that can be made with each instrument.

Flute

- It is hard to be a shy flute player if you like to hide! If you do like a bit of attention, there is also the option to play piccolo in bands and orchestras (i.e. you can be heard over the whole ensemble).

- Student flutes are relatively affordable, but professional flutes are significantly more expensive than other 'common' instruments such as clarinets and saxophones.

- One of the benefits of flute is that it does not use a reed, eliminating the ongoing cost and maintenance associated with reeds.

- One of its downfalls is that lots of people play flute, so competition and space is at a premium.

Oboe

- The oboe is a double reed instrument.

- It is a beautiful orchestral staple instrument. Like flute, it is hard to hide on the oboe. Oboists often get slow (and often famous) solos in orchestra.

- Not many students take up oboe, especially compared to flute and clarinet, and this means that for the student who likes opportunities, oboe can be a licence to print money.

- Which is just as well, because oboes can be expensive. So can reeds (which should come from a handmade/handfinished source, not a factory). Students who continue on oboe will learn how to make their own reeds, which is a great idea because they can take control of their playing more, and reeds are much cheaper in the long run.

Clarinet

- Clarinet is one of the 'common' instruments, often taught in primary schools along with flute and trumpet.

- Student clarinets are fairly affordable, and professional clarinets are often cheaper than student oboes.

- The clarinet uses a single reed, which is an ongoing expense, but they come in boxes of 10, and if looked after, a box can last a young student up to a year.

- Clarinets are needed in large numbers in bands, so even though a lot of students play clarinet, they are still able to play in more groups.

- Clarinets have 'ring keys', which are holes surrounded by rings, and the student needs to have large enough fingers to cover these holes, and have hands big enough to reach to the lowest keys. It is best to seek the advice of a teacher if you are not sure about size vs instrument. The average 10 year old can cope with the clarinet, and there are smaller clarinets available for students as young as 5.

- I consider clarinet to be a bit of a 'herd' instrument - in schools, the students will play in large sections in the band and may participate in clarinet 'choirs', and is a great choice for the student who likes to be part of a team.

Saxophone

- Student models are not as cheap as flutes and clarinets, but are cheaper than oboes and bassoons.

- Typically, the saxophone is started later than the above instruments because of the weight (the average 11-12 year old can cope with the weight of the saxophone). Students will generally start on alto saxophone, the second smallest in the family of four (standard use - there are many more!)

- Saxophone is a loud instrument, so be prepared for the practice sessions!

- It is an instrument that is easy to progress quickly on, and has a fairly simple fingering system.

- It also uses a single reed, so the same rules as clarinet apply.

- Saxophones are not used in the orchestra, so the choices of ensembles later in learning are limited to concert and jazz bands, but the saxophone is used in jazz and rock, if you would like to go that way. It is often used as a blending instrument, and despite it being loud, can be a good instrument for a less confident student, or one who likes to work in a team (there is a lot of saxophone ensemble music available).

Bassoon

- The roads ahead are paved with gold if you play the bassoon!

- Bassoons are expensive (I recommend renting one initially, or use a school instrument in the case of a high school student).

- They are a double reed instrument, like oboe, and reeds can be expensive, until you learn to make your own.

- Bassoon is relatively easy to make a nice sound on. The instrument itself has a LOT of keys, and students who are interested in 'how things work' tend to do quite well on it, though the fingering system itself is still logical.

- Not many people take up the bassoon. Bassoonists won't need to look for opportunities to play; instead, they have to turn offers down! Bassoon is the instrument for the student who likes to be different and relishes a variety of opportunities. The bassoon is a little heavy and it is usually best to wait until 11-12 years of age to start playing, depending on the size of the child.

My child is too young/small to start on their instrument of choice...what do we do?

There are a number of options if your child shows an interest in music or a particular instrument. Probably the most important step is to get them reading music and understanding things such as pitch and rhythm. For this, piano is a great starting point, because it is visual as well as aural. If your child is very keen to start on a wind instrument, the options are:

There are a number of options if your child shows an interest in music or a particular instrument. Probably the most important step is to get them reading music and understanding things such as pitch and rhythm. For this, piano is a great starting point, because it is visual as well as aural. If your child is very keen to start on a wind instrument, the options are:

- Recorder. Fingering systems on wind instruments are very similar to recorder, and if taught properly, there are techniques which are transferrable.

- Fife. Students as young as 3-4 can start their flute lessons on a fife, which will give them a chance to learn how to produce a sound without the size and weight of a flute.

- Jupiter Prodigy flute.This model can be played by students from about 5 years old who don't have long enough fingers to stretch across the keys of a standard flute. The fingerings are the same, but a clever system of extension keys has reduced the distance between the keys.

- KinderKlari. This is a small clarinet with a reduced number of keys for students around 5-8 years old. It is pitched in Eb, unlike the standard clarinet, which is pitched in Bb, which is the reason it can be smaller. KinderKlari needs to be taught by a teacher who either has an Eb clarinet or is comfortable transposing on their own instrument - check with your local clarinet teachers.

- Guntram Wolf produces instruments such as the Mini-Bassoon and simple-system oboe. These are designed for young students, and if you have a child who is begging to pick up either of these instruments, this might be a way to start. Renowned oboe maker Howarth has released a Junior Oboe, which has a reduced number of keys and is much lighter.

If you still have questions, it is best to find a good wind teacher in your area, chat to them about you/your child and get to know the instruments up close. YouTube is a great source for being able to hear and see the instruments as well.

Have fun choosing your instrument!

Labels:

bassoon,

choosing,

clarinet,

flute,

instruments,

learning,

oboe,

personality,

saxophone

Thursday, May 9, 2013

Apps for Musicians - Part Two

Welcome to Part Two of the Apps for Musicians posts! Part One focused more on apps that replaced devices that you may have once carried separately, so consider the following as bonus resources, rather than device replacements.

Fingering charts

Fingering (Patrick Q. Kelly - AppStore) - $7.99

If you take band or orchestra, have to deal with teaching other instruments or simply have an interest in learning other instruments (guilty as charged), this is a brilliant app. While not 100% accurate, it offers fingerings for woodwind and brass instruments, including alternatives and trills. If you have time and access to a computer, I highly recommend http://www.wfg.woodwind.org/, but in lessons/rehearsals/on the run, this is ideal. It is sometimes awkward to make the note slide to the chromatic pitches (it's a sensitive sideways motion), but you get better at it the more you use the app. I believe the app is also available in reduced form for a lower price, by separating out the woodwind and brass fingerings into different apps if you only need one or the other, and he also has a string fingering app.

If you take band or orchestra, have to deal with teaching other instruments or simply have an interest in learning other instruments (guilty as charged), this is a brilliant app. While not 100% accurate, it offers fingerings for woodwind and brass instruments, including alternatives and trills. If you have time and access to a computer, I highly recommend http://www.wfg.woodwind.org/, but in lessons/rehearsals/on the run, this is ideal. It is sometimes awkward to make the note slide to the chromatic pitches (it's a sensitive sideways motion), but you get better at it the more you use the app. I believe the app is also available in reduced form for a lower price, by separating out the woodwind and brass fingerings into different apps if you only need one or the other, and he also has a string fingering app.

Woodwind Fingering Chart (Adam Foster - Google Play Store) - FREE

This is not nearly as pretty as the AppStore app, and still appears to be in the developmental stages, but if it's free, it's hard to complain. It only includes flute and clarinet fingerings at this stage. It is not explicitly clear where each of the keys are unless you are familiar with the instrument in question (and the app got poor reviews from beginner instrumentalists for this reason).

This is not nearly as pretty as the AppStore app, and still appears to be in the developmental stages, but if it's free, it's hard to complain. It only includes flute and clarinet fingerings at this stage. It is not explicitly clear where each of the keys are unless you are familiar with the instrument in question (and the app got poor reviews from beginner instrumentalists for this reason).

There are also numerous free apps in the Google Play Store from Joseph Pavlick, and in the AppStore by Obie Leff. They are available on a per instrument basis, and look fairly clearly formatted. I haven't tried them for accuracy myself, but feel free to check them out!

Music terms

Music Dictionary (Tomsoft - AppStore) - $4.99

I am yet to find a music term that has been discovered in a piece of music that hasn't been listed here. Easy to use scrolling interface. There are a couple of music dictionary apps for Android, but this one is so good I haven't worried about trying them yet. When I do, I'll let you know!

IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library

iClassical Scores (AppStore) - $1.99

iClassical Scores (AppStore) - $1.99

IMSLPDroid (Google Play Store) - FREE

IMSLP is one of the most amazing resources for classical musicians on the interwebs at the moment. It is an insanely huge database of public domain music which has been scanned and uploaded to the website. You can search for works and download the PDF to the app for future reference. This app is best suited to a tablet due to the need to read music from it, but if you interested in searching on the run, it is still a valuable resource. I have used the Android version of this app, but my best guess is that the Apple version works in much the same way. You may find it useful to get yourself acquainted with the website itself, if you haven't already, before using the app, but it isn't necessary. You will need data access (3G/4G or WiFi) for this app.

Listening

Spotify (Spotify Ltd - AppStore and Google Play Store) - FREE+

Spotify is an amazing resource for recordings of all genres. The app itself is free, but unless you have access to a computer, you will need to sign up for a membership (monthly fee). The reason for this is that Spotify does not offer selective streaming to mobile devices, so unless you create playlists from your computer and listen to those on your mobile device (which you can do with a free membership) you will need to subscribe. Spotify is basically a database of albums, and there is a ton of classical music on there, usually several (or hundreds, if we are talking Beethoven symphonies) recordings of a single work. You can create playlists, which you can download to a mobile device for offline listening, and you can share with friends and through Facebook. If you are at the stage of analysing the nuances between different interpretations of a work, this is one way to access them without having to pay for them individually. You will need data access (3G/4G or WiFi) for this app.

Cloud storage

Google Drive (Google - AppStore and Google Play Store) - FREE

If you are already a cloud storage user, insert your preferred provider above. If not, and you already have a Google account (which you need to set up an Android device), Google Drive is easy to use and accessible from a range of sources. The app is available for both Apple and Android users. You will need data access (3G/4G or WiFi) for this app.

'Er, what does this have to do with music?' you may ask. Directly, nothing. But I use my Drive for many music and teaching related purposes. If you don't know what cloud storage is, the short answer is that it is data storage available to you that lives in cyberspace instead of taking up physical memory on your computer. Google Drive is also a word processor and spreadsheet creator, which was actually its function before it expanded to become general storage. Cool, huh?

I use my Drive to:

*Store worksheets for students (in PDF format)

*Store scanned sheet music so I don't have to carry books

*Store mp3s so they don't take up physical room on my device

*Share the above with students and teachers

*Keep teaching records (for students, Drive is great for keeping practice records)

*Keep lists of repertoire

*Maintain collaborative documents with teachers and students

*Back up resources I keep on my computer (such as student records, PDFs and Sibelius files)

Google gives you 5GB of storage for nothing, and you can upgrade for a fee if you need more.

There are many more examples of all of these apps, but these are the ones I have used successfully in my teaching and my own practice. If you know of others that are as valuable as these or you'd like to see apps from a category I may have missed, let me know, and there may be a sequel!

Fingering charts

Fingering (Patrick Q. Kelly - AppStore) - $7.99

If you take band or orchestra, have to deal with teaching other instruments or simply have an interest in learning other instruments (guilty as charged), this is a brilliant app. While not 100% accurate, it offers fingerings for woodwind and brass instruments, including alternatives and trills. If you have time and access to a computer, I highly recommend http://www.wfg.woodwind.org/, but in lessons/rehearsals/on the run, this is ideal. It is sometimes awkward to make the note slide to the chromatic pitches (it's a sensitive sideways motion), but you get better at it the more you use the app. I believe the app is also available in reduced form for a lower price, by separating out the woodwind and brass fingerings into different apps if you only need one or the other, and he also has a string fingering app.

If you take band or orchestra, have to deal with teaching other instruments or simply have an interest in learning other instruments (guilty as charged), this is a brilliant app. While not 100% accurate, it offers fingerings for woodwind and brass instruments, including alternatives and trills. If you have time and access to a computer, I highly recommend http://www.wfg.woodwind.org/, but in lessons/rehearsals/on the run, this is ideal. It is sometimes awkward to make the note slide to the chromatic pitches (it's a sensitive sideways motion), but you get better at it the more you use the app. I believe the app is also available in reduced form for a lower price, by separating out the woodwind and brass fingerings into different apps if you only need one or the other, and he also has a string fingering app.Woodwind Fingering Chart (Adam Foster - Google Play Store) - FREE

This is not nearly as pretty as the AppStore app, and still appears to be in the developmental stages, but if it's free, it's hard to complain. It only includes flute and clarinet fingerings at this stage. It is not explicitly clear where each of the keys are unless you are familiar with the instrument in question (and the app got poor reviews from beginner instrumentalists for this reason).

This is not nearly as pretty as the AppStore app, and still appears to be in the developmental stages, but if it's free, it's hard to complain. It only includes flute and clarinet fingerings at this stage. It is not explicitly clear where each of the keys are unless you are familiar with the instrument in question (and the app got poor reviews from beginner instrumentalists for this reason).There are also numerous free apps in the Google Play Store from Joseph Pavlick, and in the AppStore by Obie Leff. They are available on a per instrument basis, and look fairly clearly formatted. I haven't tried them for accuracy myself, but feel free to check them out!

Music terms

Music Dictionary (Tomsoft - AppStore) - $4.99

I am yet to find a music term that has been discovered in a piece of music that hasn't been listed here. Easy to use scrolling interface. There are a couple of music dictionary apps for Android, but this one is so good I haven't worried about trying them yet. When I do, I'll let you know!

IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library

iClassical Scores (AppStore) - $1.99

iClassical Scores (AppStore) - $1.99IMSLPDroid (Google Play Store) - FREE

IMSLP is one of the most amazing resources for classical musicians on the interwebs at the moment. It is an insanely huge database of public domain music which has been scanned and uploaded to the website. You can search for works and download the PDF to the app for future reference. This app is best suited to a tablet due to the need to read music from it, but if you interested in searching on the run, it is still a valuable resource. I have used the Android version of this app, but my best guess is that the Apple version works in much the same way. You may find it useful to get yourself acquainted with the website itself, if you haven't already, before using the app, but it isn't necessary. You will need data access (3G/4G or WiFi) for this app.

Listening

Spotify (Spotify Ltd - AppStore and Google Play Store) - FREE+

Spotify is an amazing resource for recordings of all genres. The app itself is free, but unless you have access to a computer, you will need to sign up for a membership (monthly fee). The reason for this is that Spotify does not offer selective streaming to mobile devices, so unless you create playlists from your computer and listen to those on your mobile device (which you can do with a free membership) you will need to subscribe. Spotify is basically a database of albums, and there is a ton of classical music on there, usually several (or hundreds, if we are talking Beethoven symphonies) recordings of a single work. You can create playlists, which you can download to a mobile device for offline listening, and you can share with friends and through Facebook. If you are at the stage of analysing the nuances between different interpretations of a work, this is one way to access them without having to pay for them individually. You will need data access (3G/4G or WiFi) for this app.

Cloud storage

Google Drive (Google - AppStore and Google Play Store) - FREE

If you are already a cloud storage user, insert your preferred provider above. If not, and you already have a Google account (which you need to set up an Android device), Google Drive is easy to use and accessible from a range of sources. The app is available for both Apple and Android users. You will need data access (3G/4G or WiFi) for this app.

'Er, what does this have to do with music?' you may ask. Directly, nothing. But I use my Drive for many music and teaching related purposes. If you don't know what cloud storage is, the short answer is that it is data storage available to you that lives in cyberspace instead of taking up physical memory on your computer. Google Drive is also a word processor and spreadsheet creator, which was actually its function before it expanded to become general storage. Cool, huh?

I use my Drive to:

*Store worksheets for students (in PDF format)

*Store scanned sheet music so I don't have to carry books

*Store mp3s so they don't take up physical room on my device

*Share the above with students and teachers

*Keep teaching records (for students, Drive is great for keeping practice records)

*Keep lists of repertoire

*Maintain collaborative documents with teachers and students

*Back up resources I keep on my computer (such as student records, PDFs and Sibelius files)

Google gives you 5GB of storage for nothing, and you can upgrade for a fee if you need more.

There are many more examples of all of these apps, but these are the ones I have used successfully in my teaching and my own practice. If you know of others that are as valuable as these or you'd like to see apps from a category I may have missed, let me know, and there may be a sequel!

Monday, May 6, 2013